COVID: Death rates in the population, and comparison with 'normal' risk (updated 15th May)

Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication

COVID: Death rates in the population, and comparison with 'normal' risk (updated 15th May)

[This article has also appeared as a Medium blog - What are the risks of COVID? And what is meant by ‘the risks of COVID’?]

As COVID-19 changes from being seen as a societal threat to a problem in risk management, it is essential that we get a handle on the magnitudes of the risk we face, and try to work out ways to communicate these appropriately. Note that I am only covering the lethal risks, not the potentially important consequences of illness or treatment.

When discussing the risks surrounding COVID, it is very important to carefully distinguish —

Fortunately new data and analyses permit more insight into these quantities, and point the way to communicate these risks. I’m going to cover the Population Fatality Rate now, finish off with a rant, and return to the IFR in a future blog.

So everything from now on refers to the risks faced by people who were not currently infected.

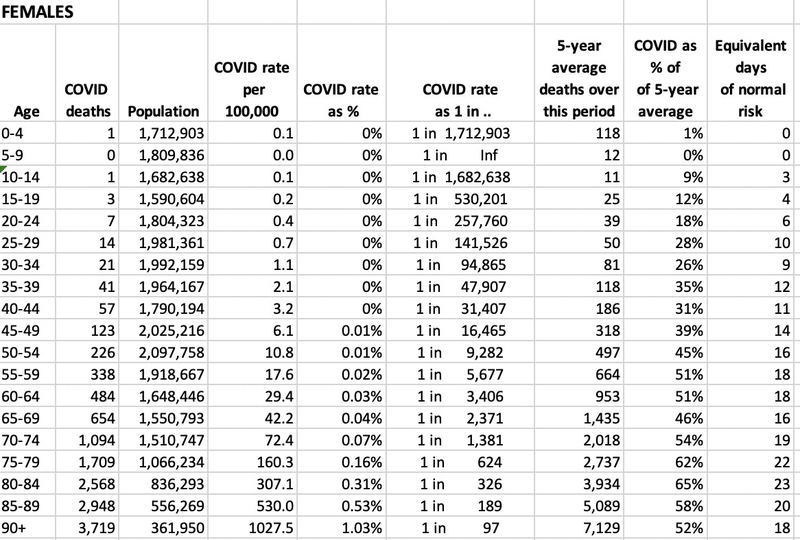

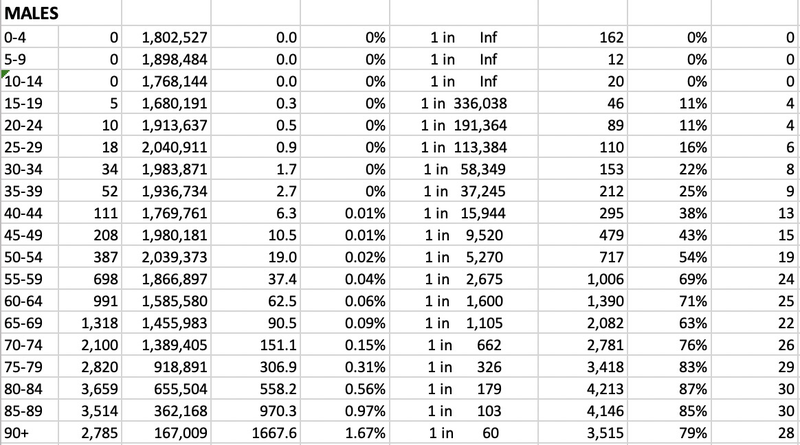

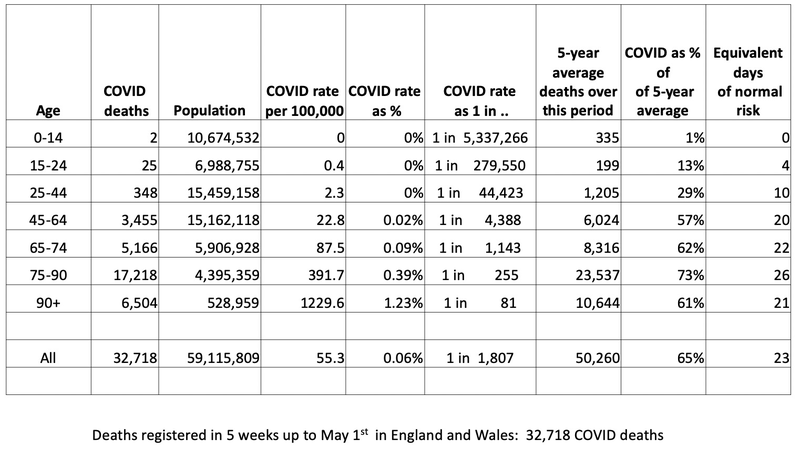

The latest data from the Office for National Statistics covers deaths registered in England and Wales up to May 1st, and the table below presents COVID population fatality rates over the peak 5 weeks of the epidemic.

It’s a complex table but worth studying.

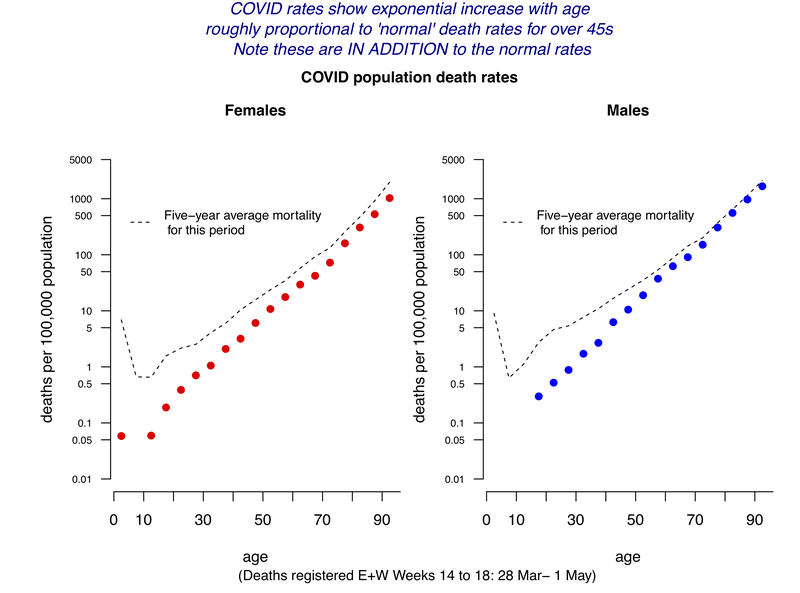

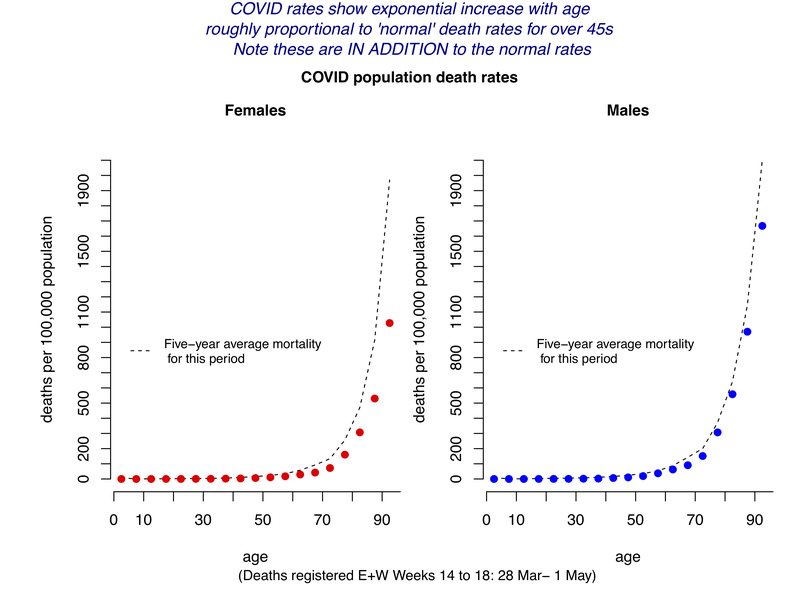

The risks differ for men and women, and a full table is provided at the bottom of the blog, and shown in the graphs below.

The amazing linearity of the data on the logarithmic scale shows that COVID rates have a fairly precise exponential increase with age, increasing at around 11–12% each year, corresponding to a doubling every 6–7 years. This means that a 20-year age-gap increased the risk by around 8-fold. So, compared to a 20-year-old, an 80-year-old had 8 * 8 * 8 ~ 500 times the risk of dying.

Men had roughly double the risk compared with women of the same age.

The extra COVID population death rates are roughly proportional (ie parallel on a logarithmic scale) to ‘normal’ death rates for over 45s, but well below normal rates for younger ages. Note these are IN ADDITION to the normal rates.

The same data can be shown on a linear scale, which better displays the huge variation of population risk with age.

Over this 5-week period covering the peak of the epidemic-

The lesser relative effect of COVID on younger groups could be partly because risks their ‘normal’ risk will be more strongly influenced by accidents and non-natural causes, whereas COVID seems to multiply your risk of ‘natural causes’ — it just seems to take any frailty and multiply it.

These are observed historical rates in the population, and cannot be quoted as the future risks of getting COVID and dying. In particular the risks of infection will be altered by factors that limit your exposure, and will be expected to drop massively as the epidemic is brought under control. In contrast we might expect the fatality rate if you become infected to remain fairly stable over time.

Please permit me a rant. It is vital for journalists and everyone else (including me) to try and avoid phrases like ‘the risks of dying from COVID-19’, as this is deeply ambiguous. As I said at the start, it crucially depends on the group it refers to, as it could mean-

These are so easily confused. An analysis last week by the Office for National Statistics reported that Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups were about twice as likely, after adjusting for some contextual factors, of dying from COVID. But this clearly referred to the population fatality rate — in other words BAME groups had a higher risk of both getting the disease and then dying from it, and an unknown part of this excess risk could come from an increased risk of catching the virus, perhaps through coming in contact with more people in their daily lives. But in the BBC 10pm News on May 7th, this was reported as BAME individuals being “90% more likely to die, if they became seriously ill with COVID-19”, which is not at all what was being claimed and could be very misleading: ethnicity was not an important risk factor for COVID patients who were hospitalised.