COVID-19 Vaccine intentions and attitudes

Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication

COVID-19 Vaccine intentions and attitudes

The Winton Centre has been undertaking research on how people think about the risks and benefits of COVID-19 vaccines and what influences their decision on whether or not to receive a vaccine. As ever, our position is 'to inform and not persuade', so - unlike many working in this area - we are not trying to increase uptake of vaccines, but instead are interested in helping people decide whether or not they want to take the vaccine.

This page details some of the studies we have been working on.

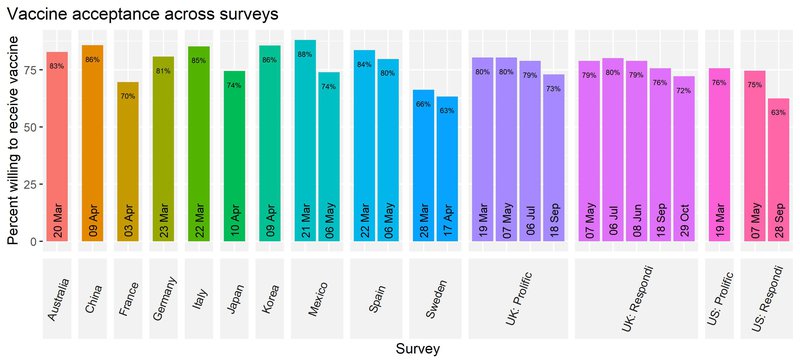

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across time and countries

Starting in March 2020, the Winton Centre has been conducting surveys on COVID-19 related issues, and in many of these surveys, participants were asked if they would be willing to be vaccinated if a COVID-19 vaccine was available (total N = 25,334). Across 25 national samples from 12 different countries, we examined the psychological correlates of willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, with a focus on risk perception and trust in a number of relevant actors, both in general and specifically regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. Across countries, we found that men, people who trust in medical and scientific experts and those who worry about the virus are more likely to say 'yes' to a vaccine. Our results indicate that the burden of trust largely rests on the shoulders of the scientific and medical community, with implications for how future COVID-19 vaccination information should be communicated.

The full study is published in the open-access journal BMJ Open, and data and analyses are available on the OSF.

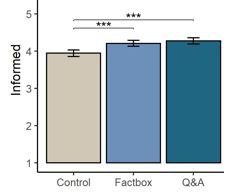

How does information change (or not change) vaccine beliefs and intentions?

In early 2021 we conducted two separate pre-registered experiments to examine how information about COVID-19 vaccines affects people. We were interested partly in people's intentions to get vaccinated and their related beliefs, but also in how they felt about the decision - did more information make them feel better informed and happier about making a choice? In one study we found that information about vaccine risks and benefits reported in clinical trial results—presented as either a set of 'factbox' tables or as a Q&A—had a limited impact on beliefs. Reading the information didn't lead to changes in peoples' perception about how well available COVID-19 vaccines 'work' or their concern over side effects. Across all experimental groups, we found no change in willingness to receive a vaccine, but we did find that people who read clinical trial results felt more informed of risks and benefits.

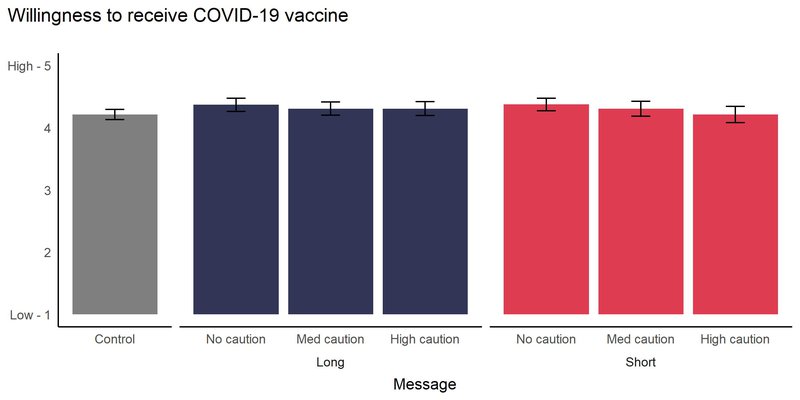

In a second experiment, we looked at how reminders about the need to continue mask-wearing and social distancing after vaccination influenced people's willingness to do so, and their intentions to get vaccinated as well as how informed people felt. Some of the messages participants read were very positive ("no caution") while others highlighted the current uncertainty about vaccine efficacy ("high caution"), and we tested 'tweet length' short messages as well as longer ones that might be used on a website. We found that highlighting uncertainty around efficacy didn't dissuade people from getting vaccinated, but also didn't increase (already high) intentions to follow public health guidance after being vaccinated. Again, we found that some messages increased how informed people felt regarding their vaccination decision, even though it didn't change their intentions.

Both experiments have been published in the open-access journal Vaccines, and data and analyses are available on the OSF.

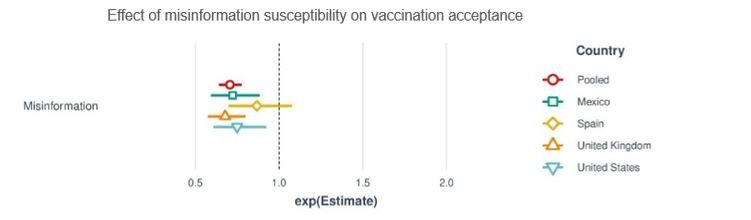

Misinformation susceptibility linked to vaccine hesitancy

Dr Jon Roozenbeek from the Cambridge Social Decision Making Lab has analysed data from several Winton Centre surveys, examining how susceptibility to misinformation is associated with willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine across several different countries. People who agreed with false claims about the COVID-19 virus (such as “5G networks may be making us more susceptible to the coronavirus”) were more likely to say no vaccination, even after controlling for a number of other factors. Taken together, the results demonstrate a clear correlation between susceptibility to misinformation and vaccine hesitancy. For those that want to increase vaccine uptake, it's possible that interventions that aim to improve critical thinking about claims may be a promising avenue for future research.

The research is published in the open-access journal Royal Society Open Science, and data and analyses are available on the OSF.

Examining the 'gender gap' in vaccine hesitancy

The Winton Centre also contributed data to a meta-analysis conducted by the Gender Studies & Health Psychology Lab at Heidelberg University. Across 46 different studies, the authors identify a clear pattern with men being 41% more likely than women to express willingness to receive a vaccine, though the reasons for this gender gap remain unclear. Further qualitative research is needed to understand why this gap exists, they conclude.

The research is available as a preprint on the SSRN server.